Blog

Are you frustrated with your eating?

In addition to my general coaching practice, I also do some work specifically for people who struggle or feel frustrated with their eating. I’ve been running small, virtual group classes called Dessert Clubs on that topic for four years now, and my next round starts in October. I only offer them twice a year, and if you’d like to learn more, you can do so here. Or, below is some more information:

Does this describe you? :

You’re a smart, capable, pretty-much-together person. Even if it’s not perfect, you’re generally happy with your career or your schoolwork or your relationships or friendships, or your parenting.

And then there’s your eating.

Your eating is this weird, complicated thing that sometimes feels…well, out-of-control.

Sometimes, when you’re alone in the house, or after everyone else goes to bed, you stand next to your kitchen cabinet and eat chips out of the bag, and it’s almost like your brain goes blank because then you eat way more than you intended to. You also really, really hope no one walks in on you right then.

Sometimes you eat three donuts from the break room at work while you’re finishing up a presentation. Even though you don’t even like donuts that much and you weren’t hungry and you promised yourself you wouldn’t do this.

It’s not like you don’t know how you “should” eat. You do! You know what’s healthy and what’s not, pretty much. You know what a “reasonable” quantity of chips or cookies or ice cream would be. You know what a healthy dinner or lunch or breakfast would be, too! And you do eat that way, a fair amount of the time.

And then there are those other times. When you don’t eat in a way that makes you feel good, and you don’t even know why.

…

I want to be really clear — I’m not saying that the problem with this type of eating is that it’s “unhealthy” or anyone who eats in this way is a bad person.

The problem is this:

You know that you’re eating in a way that doesn’t serve you, and you can’t seem to stop doing it.

The tragedy of all of this is that we are often genuinely hurting ourselves. Sometimes physically — we may make ourselves feel bloated or sick. But certainly emotionally, too — we might feel anxious or guilty, or worry about our eating all the time. Many of us will go on diets or eat less to try to “make up for” our indulgences, and it can sometimes feel like it takes an insane amount of brainpower and effort, and energy to deal with our eating and our weight.

If that feels like you — if you are exhausted and annoyed and tired with all of the ups and downs of your relationship with food — I want you to know this:

1. It’s not just you.

It’s not just you. It’s really not. This kind of eating is sadly common, across genders and age groups — though I find that it is particularly common with women because society’s strict messages about body size can set off a chain reaction that eventually results in many of us having unhappy relationships with food.

Even though most people don’t talk about it, many people feel alternately exhausted (with all the effort it takes to “manage” frustrated eating) and annoyed (because they, inevitably, over-eat, and want to kick themselves).

2. You don’t have to feel this way forever.

You really, really don’t. It is possible to have a relationship with food where you consistently eat in a way that supports your overall well-being — so yes, sometimes that means healthy or nourishing foods, but at other times that means foods that give you pleasure or enjoyment, and in a quantity that also makes your body feel good.

But in order to stop, you have to understand why you do this.

In the past, when I would overeat and sometimes feel out of control, I would feel so guilty and promise myself that I wouldn’t do it again. But of course, I did do it again, because just resolving to “not do it again,” doesn’t do anything to address the deeper, underlying reasons why I did it in the first place.

Actually healing your relationship with food requires a deep examination of why you eat the way you do. It also requires taking action — to interact with food differently from the “just stop overeating!” way we’re used to doing it.

That is the core work of the Dessert Club — small group classes that I’ve been running for four years now (!!), and which start up again in a couple of weeks.

In the lead-up to the Dessert Club, my newsletter will have more essays about eating, the deeper meaning behind why we over-eat or sometimes feel out-of-control around food, and what you can do about it.

And, of course, if you really want to do something about it, I’d urge you to consider joining a Dessert Club. I only offer these groups twice a year! Here’s what one past participant said:

"I used to wake up and plan each meal that I would eat, how many calories I could eat, the times I was allowed to eat, etc. Of course, I used to break these rules all the time because I would feel hungry and then feel angry with myself.

But ever since I learned about intuitive eating from you I've stopped overeating and the stomachaches have stopped! I feel so happy every day waking up knowing that I can eat whenever and whatever I want as long as I'm hungry and I stop when I'm full. No gimmicks, dieting, restrictions, guilt -- it's wonderful to feel free.

Thank you, thank you SO much, Katie, for leading such wonderful sessions! You truly changed my life and helped me out of a cycle I thought I'd be stuck in forever. I'll certainly recommend the Dessert Club to anyone I know who is struggling with food. Thank you!"

Here’s information on the upcoming groups:

Tuesdays, starting October 8

4 pm PST/7 pm EST

Learn more

Wednesdays, starting October 9

7 pm PST/10 pm EST

Learn more

And no matter what path you take with all of this, please know that I’m rooting for you.

Katie

Meditation + people with anxiety

I’ve meditated, on-and-off, for many years now. But unlike some of my other habits (like this or this), I never quite made it a consistent, long-term practice. Until I read this:

“I’ll say it dead straight, because this is how it was presented to me: when you’re the anxious type, meditation is non-negotiable.”

(That quote is from Sarah Wilson, in her lovely book on anxiety, First, We Make the Beast Beautiful.)

Wilson doesn’t say that meditation will 100% cure a tendency towards anxiety. It doesn’t.

But does it help? Yes, it does.

So I’ll ask: are you the anxious type?

As always, I’m rooting for you. You’ve got this.

Katie

The Robot Fantasy (or: one reason you "can't get things done")

Many people I meet have something I call “the robot fantasy.” As in: they’d like to be a robot.

Of course, if you casually asked, “would you like to become a robot?” they’d laugh and say no. But then, later, they’d find themselves deep in fantasy:

I wish I could just get my entire, 16-point to-do list done every weekend.

I wish I could just work at my intense job, pursue my passion project with vigor, be a good friend and partner, exercise, and make healthy, delicious food — every single day.

I wish I could stop getting physically and emotionally tired!

In other words: I wish I could stop being a human!

Humans are, by nature, not robots. Yes, we can accomplish a great deal. Yes, we can check items off a to-do list. But we can’t just program ourselves — beep bip boop — and then expect ourselves to execute whatever plan we come up with. Even if there’s technically enough “time” to work and exercise and do everything our kids need and sleep and remember to buy that birthday gift…we may not be able to do it.

Because we’re also stoppable. We have emotions and thoughts and we need time to rest and re-charge — often more time than many of us think we “should” need.

(Saying that you “shouldn’t” need so much time to rest, of course, is another way of saying I wish I was a robot.)

Sometimes the first step to building a life that works better for you means admitting:

Fine, I will never be a robot. So what can I do with my measly humanness?

As always, I’m rooting for you. You’ve got this.

Katie

5 ideas for finding more friends as an adult

Last week I wrote about friendship, loneliness, and why it’s not surprising that you might need a new friend or two.

This week, I wanted to share five ideas about how to actually make those new friends, all from Shasta Nelson’s lovely book, Friendships Don’t Just Happen: The Guide to Creating A Meaningful Circle of Girlfriends. They’ve been helpful for me in my process of making new adult friends, and hopefully, they’ll help you, too:

1. Long-distance friends aren’t the same as local friends.

Many of our long-distance friends are very important to us. We’ve known them a long time, and have a deep intimacy with them. That’s great!

But, Nelson argues, long-distance friends aren’t a substitute for local relationships. Even if you talk on the phone regularly, and see each other once or twice a year, it’s nearly impossible to be creating as many new memories or sharing our day-to-day lives in the same way as you could with a local friend. For that reason, Nelson considers long-distance friends to be a separate category of friends — she calls them “confirmed friends.”

Realizing this was a big shift for me. I have a number of close friends living across the country from me, who I’ve known for a long time and deeply value. Of course, I have no plans of losing touch with them and I hope to have them in my life for a long, long time. But Nelson’s argument made me realize that if I plan to live in Los Angeles long term — which I do — I have to develop a stronger circle of close, local friends.

2. If you want to have close friends, you have to start with friendly acquaintances.

I’ll admit: What I truly want is a handful of close, intimate friends. The kinds of friends who celebrate birthdays together and call to check in if we know the other is having a stressful week. The kinds of friends who I can be truly honest and authentic with. I have some of those, but could use a few more where I live.

But Nelson’s book pointed out that the only way you get to close, committed friends is by making friendly acquaintances first. She has a great model of friendship as a five-stage spectrum (you can see the full model here) from acquaintances on the left to deep, committed friends on the right.

Her point is that all friendships — no matter how deep or intimate they may eventually be — start out as friendly acquaintances. Some friendships will progress through the stages of increasing depth and intimacy, and some won’t. And, frankly, it can be hard to tell at the beginning which ones will make it all the way to what she calls “commitment friends,” the deepest level of friendship.

But you have to start out with a lot of casual acquaintances and see who goes deeper over time. As someone who loves deep connection, this was a little tough to accept.

But it was also a relief — it reminded me that it’s normal if none of the people I meet “feel like” close, intimate friends. They aren’t that kind of friend! They will only feel like friendly acquaintances. And then, as I invest in those relationships, we’ll see what they become.

3. The two most important characteristics of a deeper friendship are intimacy and consistency.

Consistency means “regular time spent together,” and intimacy means “sharing that extends to a broad range of topics and increases in vulnerability.” I think this makes a certain amount of intuitive sense: the more time you spend with another person, and the more you both share intimately with each other, the deeper your relationship will become.

But notice what this definition excludes: how much we like each other.

The truth is that even if you really like another person and they like you, you might not become friends. How often have you met an interesting person, had a fun or deep conversation, and thought hey, I’d like to see them again! And then you never saw them again or never saw them frequently enough to actually become friends. If there’s no consistency there (and intimacy, of course), you won’t become friends.

Of course, how much you like the other person will influence whether you’re willing to be consistent and intimate with that person. But there could be people who you like quite a lot, and still the friendship never quite gets off the ground. It is the consistency and intimacy which are bedrock requirements.

As a result…

4. You’ll have to initiate. And initiate again.

Nelson points out that women, in particular, may enjoy being pursued, and may be used to having someone else initiate other key relationships:

“In romance, we want to be pursued. In job interviews, it’s up to the HR team to make the offer. But in friendship, there isn’t a clear conductor of this symphony, a leader in the dance. We’re just two women who probably could use more support in our lives, but if we both sit back and hope the other reaches out, then I’m afraid that we’ll end up with a company of disconnected, depressed, lonely women… So we’re going to initiate. Yes, we are. Again. And again.” (107)

Most people I know are comfortable initiating at least once. Maybe even twice. But pretty soon, we start to keep score: I initiated last time, it’s her turn this time.

Nelson’s radical point is that we may have to initiate, and then initiate again. And then a third time and maybe a fourth. Of course, we shouldn’t initiate every day, and we should pay attention to signals from the other about whether they’re interested in our friendship. But if we don’t see each other regularly (point #3), a friendship will never take off. So if we want more meaningful relationships in our lives, we may have to initiate more often than our initial instincts would go for.

5. One last thing

Here’s some tough love, from Shasta Nelson:

“If you tell me that you want to foster more meaningful friendships, then my response back to you will always be: tell me who you have scheduled in the upcoming two weeks and I’ll tell you if you’re on your way to stronger friendships.”

The only way to make more friends is to spend time with potential friends. There is no substitute. And given how busy most people are, this time often must be scheduled in advance.

…

Was this helpful? What are your takeaways? I’d love it if you’d leave a comment below.

And as always, I’m rooting for you in the week ahead.

Katie

If you're feeling lonely, here's a concept that helped me

I’ve had two big moves over the past few years — from New York to North Carolina, and then from North Carolina to California. Both times, after the initial exhilaration of a new home wore off, I looked around and realized I had very few, or no, friends where I lived.

So I started to try to make more friends. I started going to more events, but every time I met someone who I was interested in getting to know more, it seemed like they already had plenty of friends. Why would they want to be friends with me?

I felt kind of needy, as I tried to initiate spending more time with interesting people.

But it turns out that lots of us need more friends! In Friendships Don’t Just Happen: The Guide to Creating A Meaningful Circle of Girlfriends, Shasta Nelson pointed out two things that really surprised me:

People, on average, replace half of their close friends every seven years, according to researchers in the Netherlands. Half! So most people you meet will probably be looking to meet at least a friend or two.

Many of us aren’t doing a great job of finding the new friends we need. A quarter of us have no one with whom we share deeply. Another quarter has only one person — likely a significant other or spouse — so we’re deeply vulnerable to a potential break-up, divorce, or death. That’s about half of us with one or zero close confidants or friends. The other half of us have an average of two.*

Nelson’s book is mostly a how-to guide for making meaningful adult friendships. And if I’m being honest: at first, admitting that I was reading a book like that seemed, well, embarrassing. Does admitting that I need more friends make me seem needy?

And yet, here’s something else that Nelson wrote, which I really needed to hear:

“Loneliness is not about social skills, likability, or the kind of friend we can be to others.”

I realized, in reading it, that I’d been subconsciously judging myself for being lonely. On a subtle level that I hadn’t been able to name until I read the book, I’d been assuming that people who are likable enough, who have strong enough social skills, and who are great friends, don’t get lonely. Have you ever felt that way?

But everyone needs new friends — frequently! And everyone gets lonely! If we’re going to replace half of our friends every seven years, we’re definitely to feel twinges of loneliness sometimes.

Nelson’s book had a couple of good, practical points about how to actually make more friends, which I’ll share next week. But for today, I just want to remind you:

Just like hunger tells you that it’s time to eat,

Or fatigue tells you it’s time to sleep,

Loneliness tells you that it’s time to put in some effort to generate new, meaningful relationships.

None of those experiences — hunger or tiredness or loneliness — necessarily have anything to do with you as a person: your worth or value or likeability.

It’s okay to be lonely. It’s normal to need new friends. And if you meet a new person who seems interesting, there’s a good chance they might be looking for a new friend, too.

*This data is from research published in the American Sociological Review in 2006, cited in Friendships Don’t Just Happen.

I’m in your corner rooting for you. You’ve got this.

Katie

Why you might be successful but unhappy (+ the chart that made me gasp)

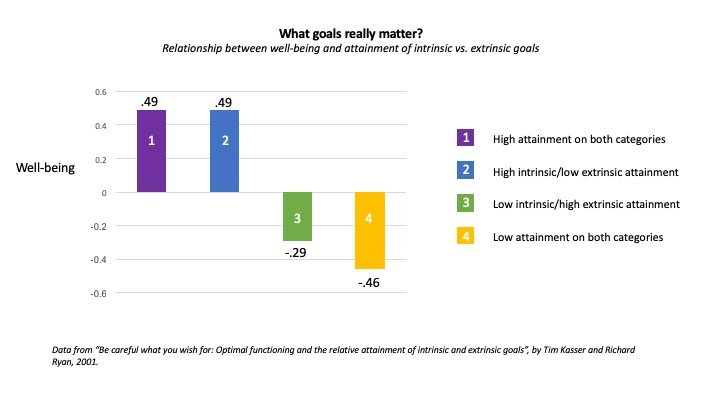

I was sitting on a plane, reading a kind-of-dry book, when I saw a chart that made me gasp.

My husband, sitting next to me, asked to see what had made me react like that. So I showed him, and his eyes widened, too.

“I can see why you gasped,” he told me.

Here’s the chart, and I’ll explain what it means in a second:

This chart is based on a study by Tim Kasser and Richard Ryan, in 2001. They were interested in the relationship between attaining certain kinds of goals and people’s well-being. In particular, they distinguished between two types of goals: extrinsic vs. intrinsic.

Extrinsic goals include wealth or admiration or fame. They are things that we do because we like how they make others view us.

Intrinsic goals includes personal growth, close relationships, and community contributions. Typically, intrinsic goals feel good in-and-of-themselves, whether or not they impress or please others.

It’s worth naming that any given goal could be either intrinsic or extrinsic, depending on your motivation. For example, someone could play the piano simply because they love it (an intrinsic goal), or because their parents said they have to (an extrinsic goal).

In this study, Kasser and Ryan asked college students how much they felt they had achieved extrinsic goals (money, fame, appearance) and how much they felt they had achieved intrinsic goals (personal growth, close relationships, community contribution.)

Then, they separated the college students into four different groups:

High achievement on both categories

High intrinsic achievement, low extrinsic achievement

Low intrinsic achievement, high extrinsic achievement

Low achievement on both categories

They also asked those college students about their personal well-being — which they calculated by asking them about things like self-actualization, anxiety, and depression.*

So, back to that chart again:

Two things made me gasp about this chart:

1. Attaining extrinsic goals doesn’t really matter for well-being.

Look at groups 1 and 2. There was virtually no difference in well-being between students who had achieved bothextrinsic and extrinsic goals (group 1), versus students who had achieved intrinsic goals only (group 2).

2. But if you haven’t attained intrinsic goals, your well-being suffers.

I think that group 3, in particular, is very interesting. Those students had high achievement of extrinsic goals, but low achievement of intrinsic goals. If you saw them, you might see them as attractive or successful. But they had terrible well-being!

In fact, there’s not a ton of differences between students in group 3 (high extrinsic achievement, low intrinsic achievement) and group 4 (low achievement on both). A small difference, to be sure — it’s better to achieve something than nothing at all — but not as much as you’d think.

…

The reason that I gasped when I saw this study was because even though I’ve heard all of the classic reminders that “being beautiful or successful can’t buy happiness” and “good relationships are what matters most,” I can still find myself wanting to achieve “impressive” things, on some level. Don’t you?

I had never seen, in such stark terms, how little those things actually matter for well-being.

And so, here’s my offering for this week: Have you reflected on your goals lately? How many of your goals are intrinsic? How many are extrinsic?

* Technically, Kasser and Ryan compared goal attainment, on the x axis, and “correlation with well-being” on the y-axis in their original study, but Kasser, in The High Price of Materialism, simplified “correlation with well-being” to “well-being,” and I’ve chosen to do the same here.

(For anyone that’s curious, I originally saw this chart in Tim Kasser’s The High Price of Materialism, p. 44-46. I fully understood the study by going back to Kasser and Ryan’s original paper summarizing the data, which you can access here.)

As always, I’m rooting for you. You’ve got this.

Katie

Two ways I use the internet less - without a full-scale digital detox

I’m very interested in how technology affects our well-being, and how we can use it more intentionally. I’ve written about this topic before (here and here), but here’s one phrase that’s been ping-ponging around my head recently:

Just because some is good, doesn’t mean that more is better.

It’s easy to read that phrase and think, Of course. Duh.

But are you actually applying it in your relationship with technology? Do you actually say to yourself, for example, “I’ve noticed that 30 minutes of this app/activity/device brings me significant benefit, but past that point, do the downsides outweigh the positives?”

To give you some ideas of how to begin that process, I wanted to share how I’ve been applying it to one part of my relationship with technology: Internet browsing.

Internet Browsing and Intentional Technology Usage

I’ll admit it: I love browsing the internet for pleasure. I use social media rarely at this point, but I still have blogs and websites that I love to read. Plus, occasionally watching SNL videos can be so fun! I think some amount of internet browsing is “good” for me because it brings me so much pleasure.

But I started noticing that because I enjoyed the internet so much, it was tempting to do it all the time. Oh, I just woke up? Why not look something up on the internet? Oh, I have a few hours after dinner? Why not spend all of it on the Internet?

I often felt like time would fly by – and like I never quite had enough of it. I also started wondering if the internet was actually giving me all the pleasure and relaxation that I thought it did.

So here are two things that I started to do, to implement “just because some is good, doesn’t mean that more is better” with my internet browsing:

1. Not using the Internet after dinner

I used to spend most of my after-dinner time on the Internet. I was tired from the day, there was nothing urgent to do, so why not? But I also noticed that I often felt emotionally tired at the end of my night, even after spending a significant amount of time online, which I thought helped me relax. I wondered whether the internet — even though it’s quite pleasurable — wasn’t letting me emotionally recover.

So I decided that I’d explore just not using the internet after dinner. Here are some of the interesting things I found:

I felt calmer. The very first night I did this experiment, I read a book for three hours after dinner, when I might otherwise have been browsing the internet. When I finished reading, I thought to myself, “Wow, I feel so much calmer than I’ve felt in a while.” I noticed that my body felt noticeably less stressed than before, and my breathing was slower. This has proved to be consistently true and is the main reason I’ve stuck with it.

I felt like I had more time. Somehow, my evenings have started to feel longer, even though they are often actually shorter, because…

I went to bed earlier. When I stayed off the internet after dinner, I kept finding myself getting tired earlier than I used to. It makes perfect sense — there’s no shortage of research on the negative effect of technology use on sleep. But it felt different when it actually happened to me.

I woke up earlier. It turns out that when you go to bed earlier, you tend to wake up earlier, too. I love mornings and had always wanted to get up earlier without sacrificing sleep, so this was a big perk for me.

I read many more books. The week that I’m writing this alone, I’ve started and finished two novels, and read some chunks of good nonfiction. This is an above-average week (the novels were both pretty fast reads), but I read a lot now.

2. Keeping a list of the things I’d like to “check” online

The internet makes it possible to get an answer to nearly any question, instantaneously. As a result, very tempting to look up the answer to any question, the moment we have it. It’s so satisfying to get an immediate answer! And it only takes a second!

But I started noticing that I was doing a lot of little “quick checks” throughout my day and wondered whether it was affecting my productivity and focus. Plus, even if the answer to my question could be professionally or personally useful, it was rarely true that I needed the answer to the question right then. I could usually wait at least a few hours for the answer.

So that’s what I started to do – I started keeping a list of “things to look up online” on a Post-it throughout my day. Then once a day, usually around 4 p.m., I look up as many of them as I please. I’ve definitely noticed that it helps me stay focused on the task at hand throughout the day, and it’s actually fun to be able to look up a bunch of things at once.

…

I like internet browsing — some of it is good for me. But using it whenever I had some leisure time wasn’t great for me, as it turned out. by not using the internet after dinner, I help myself have a calm and spacious, and more truly rejuvenating end to my day.

Similarly, I like being able to look up answers to my questions on the internet — some of it is good for me. But batching it helps me make sure I’m focused on what matters, rather than getting micro-distracted throughout my day. I can still get the answers to any questions that matter — I just have to wait a bit.

I’ll also say that I don’t do either of these practices 100% of the time. I’m not perfect, by any means. The good news is that I don’t have to do them 100% of the time, to experience real benefit.

How could you implement “just because some is good, doesn’t mean that more is better” in an actionable, concrete way in your life?

As always, I’m rooting for you. You’ve got this.

Katie

Ever have a vague sense that something is "off"? Don't ignore it

Sometimes what’s wrong feels nebulous:

It’s a subtle feeling of “not-rightness” that we only get in moments when we don’t have a lot to do.

It’s a nagging feeling in our belly that we need to make a change.

It's like we can only “see” what’s wrong out of the corner of our eye. And it's blurry.

Even more confusingly, we might feel fine a lot of the time! We go to work, spend time with our friends, our partners, go to the gym, and enjoy delicious meals. A lot of our lives are great!

And yet, we can’t shake the feeling: Something isn’t right. Something is “off.”

Here’s my suggestion: don’t ignore that feeling.

That feeling is important. It’s even life-affirming, even though it might also feel vague and confusing. But precisely because it's vague and confusing, and because there are concrete things that we've gotta get done in the here and now — laundry to do, reports to write, friends to see — we have a tendency to push it aside. I'll deal with it later, we think.

And then we never actually deal with it later.

Here’s what I know for sure about this nebulous feeling of not-rightness: you have to stay in the question.

“Staying in the question” means not ignoring it. In fact, "staying in the question" means revisiting this feeling that something's off and asking, What’s wrong? and What needs my attention? and What am I resisting?

Feelings like this respond well to patient curiosity, but it may take some time. (And, of course, support can be quite helpful.)

As always, I’m rooting for you. You’ve got this.

Katie

This might be why you're feeling stuck in life

When I studied improv comedy in my early twenties, teachers always emphasized “playing at the top of your intelligence.” Even if your character isn’t a Nobel Prize winner, “playing at the top of your intelligence” means that in every situation, she’s trying to be as smart and savvy as she can with what she’s got.

People who are playing at the top of their intelligence are more compelling to watch. The plots of their stories are more likely to move forward and not get bogged down in repetitive, boring, unnecessary stuff.

Are you playing at the top of your intelligence?

Many of us aren’t.

Many of us know, on some level, what’s working and not working about our lives. If we had a half hour of quiet to reflect, we could make a pretty accurate list of the things that are going great and the things we’d like to work on to have lives that are happier, healthier, more meaningful, or more productive.

Many of us don’t do that kind of reflection very much. We may think it’s because we “don’t have time,” but most of us have plenty of time for Netflix or YouTube or whatever our technological pleasure might be. I suspect the real reason might have more to do with how uncomfortable it can be to see ourselves clearly or how making changes might require time or energy or shaking up parts of our lives. We might have to seek out help to figure out our next steps.

The end result of avoiding this reflection and truth is the same: We’re not playing at the top of our intelligence.

But remember what happens with characters who do play at the top of their intelligence? They’re more compelling to watch. The plot of their lives moves forward and doesn’t get bogged down.

Isn’t that something we’d all like?

As always, I’m rooting for you. You’ve got this.

Katie

It's okay to change your mind

Here’s a reminder:

“You always have the right to change your mind.”

Even if you’d done something a certain way in the past…

Even if you thought something different before…

You still have the right to change your mind.

Now.

Here.

Today.

(That quote is from the always-wise Oprah, in this generally delightful video)

I’m rooting for you.

Katie

8 Differences between life coaching and therapy (from someone who has done both)

I’m a coach, and I’m often asked: “How is coaching different from therapy?”

It’s a good question, especially because coaching is a newer profession than therapy, and less familiar to many people. In order to begin to answer it, though, I have to ask a different question:

How are you defining “therapy” and “coaching”?

There are a wide range of approaches in both therapy and coaching. An art therapist is not the same as a somatic therapist is not the same as a Jungian psychotherapist. Similarly, a writing coach is not the same as a financial coach is not the same as an Integral coach.

As a result of this, coaching and therapy can be extremely different (e.g., there might be very little overlap between a business coach and an art therapist). Or they may have many similarities. To be honest…

The modality of the practitioner likely matters more than therapist vs. coach.

I’ve been in therapy and worked with a range of coaches. The first coach I ever worked with was an Integral Coach, whose work really changed my life. Several years later, I worked with a therapist who worked across a range of methodologies. While there were some important differences — which I’ll discuss below — there were more similarities, and I had a positive experience with both.

On the other hand, I briefly worked with a business coach, and that experience was extremely different from either my Integral Coaching or therapy experiences. I’d also imagine that if you worked with a Cooking Coach, for example, it would also be quite different from therapy.

For the rest of this essay, I’ll be talking about the differences between some generalized definitions of “therapy” (more on that below) and Integral Coaching. Integral Coaching form of coaching I am most familiar with — I’m a trained Integral Coach, and I’ve worked with several Integral Coaches.

Please remember that there are as many different types of therapy and coaching as there are practitioners, so for everything I say about therapy or coaching, there will be many exceptions. It’s nearly impossible to generalize across such large fields without simplifying, and I am, of course, making this analysis based on my personal experience and conversations with others. However, I think it can be useful for some people to understand some broad differences, so I’ll share how I best understand those differences.

Here are some of the big differences between coaching and therapy that I have noticed (again, with some important caveats at the bottom of this post):

1. Therapists are uniquely qualified to help people with psychological disorders or who are healing from serious trauma.

For example, if you suffer – or think you may be suffering — from schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or are healing from childhood sexual abuse, a therapist will have the best training to support you. Coaches simply aren’t trained to work with people with these types of challenges.

2. Coaches only work with people who are functioning or highly functioning in the world.

When we’re mostly “functioning” in the world, that means that we’re paying our bills, showing up to work, and mostly meeting our commitments to others. Or maybe we’re even highly functioning — other people, from the outside, might think that we’re really “together” or successful or happy.

But even if we’re functioning or highly functioning, we may still have a nagging that something isn’t right in our lives. Maybe we’re feeling stuck or lost, or maybe we keep putting off taking action toward what we want. Maybe we’re having some big feelings — like sadness or anxiety — and we’re not sure what to do with them.

Just because we’re functioning or highly functioning doesn’t mean we don’t have personal work to do. Coaches can be a great fit for people in this situation.

3. Coaches may expect more engagement from you.

Past clients have told me that they’ve been in therapy before, and felt like they showed up every session and shared about their feelings or their past. The therapist was often a compassionate listener, but the patient didn’t necessarily feel like they “changed.”

In my experience, my work with coaches has generally felt more active or potent than therapy. Part of that is because coaches expect more of you. You’ll be doing work in between sessions — which could include reading books or articles, watching videos, trying out new practices, or journaling to reflect on a key question that has come up.

When clients do work in between sessions, they have new observations about themselves, which makes future coaching sessions more productive. They also experiment with behaving differently in the world — for example, trying new actions to be more confident at work, or trying new techniques to resolve conflict better in relationships. In my experience, when you act differently and have new observations about yourself, you will change much faster than by simply talking for forty-five minutes or an hour once a week.

And, of course, some coaching clients don’t have the time or energy to do work in between sessions. That’s okay too — the coach would start by helping them make space in their lives. If they don’t have time for coaching homework, it’s probably a sign that they’re stressed, overwhelmed, or need some more free time, anyway.

4. Coaches may be more explicit about your development path

In the first few sessions of a coaching engagement, we would work together to explicitly define: (1) the skills you will develop, and (2) how the world will feel to you, as a result of our work together. We write down that development plan and check in with it throughout the coaching program.

That means that two months later, for example, we can notice which categories you’ve made progress on, and which need more attention. That document also helps us know when you’re done with coaching — when we realize that you’ve made significant progress in each of the major categories, it’s time to wrap up the coaching engagement.

5. Coaches may be more engaged with you.

Some clients have told me that their past therapists mostly listened, and preferred not to share their observations or ideas even when the patient asked their opinion. (Again, this is not true of all therapists; see below.)

While the goal of coaching is for you to develop the capacity to observe yourself and change on your own, as a coach, I am typically a bit more involved. Many of us have blind spots about ourselves that we can’t see — so as a coach, I would compassionately share with my clients what I notice about them, that they may not be able to see about themselves. Especially in the first half of the coaching engagement, I would also recommend the actions, reflections, or changes that I think might make sense for them to take next.

Of course, the goal of coaching is for the client to develop the skills to change independently of a coach. But I think that one of the great advantages of working with a coach — instead of trying to change on your own — is that the coach can notice things about you that you can’t notice about yourself. So I am actively, but compassionately, engaged in sharing that with you (and, in my experience, this is a satisfying experience for a client. I’m not harsh or unkind — typically, sharing my observations is a helpful thing for a client).

6. Coaching may be shorter than therapy.

To be clear, this is a generalization, but multiple coaching clients told me that they were in therapy for a year or more — sometimes even multiple years.

It would be very uncommon that a coaching engagement would go on for longer than a year. When this has happened, it is typically because the client has achieved their goals (see #4), but wanted to work on some new things together. The average length of my coaching engagements tends to be six months.

7. The roots of the professions are different.

Therapy’s roots are in the medical field. One of the major guiding forces of the field is and has been the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), which classifies mental disorders. Typically, if therapists want to be paid through insurance companies, they must assess their patients as having one of the mental disorders listed in the DSM — even though they might not share that diagnosis with the patient. Of course, not all therapists prefer to think of their patients in terms of the “mental disorders” they have, but the roots of the field do follow this path, and this is why only therapists are qualified to support folks who struggle with mental disorders like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

Modern coaching has a number of different origins, but one major origin is sports coaches (more on sports and coaching here). As a result, there is a history of working with people who are already competent — and sometimes quite highly functioning — and helping them reach the next level. There is less of an interest, in the history of the field, in thinking about disorders, and more of an interest in just figuring out what is blocking functioning people and helping them grow.

8. Coaches often work over video conferences.

This is increasingly common for therapists as well, but therapists can often only work with people over video conference who are in the same state as them. As a coach, I can work with clients all around the world — and have! (I’ve had clients on five continents so far!)

I’ve also personally worked with several coaches of my own — coaches need their own coaches! — who lived in different states or countries than me. At first, I was a bit hesitant — can working with a coach over video conference be as effective as meeting in person? I found that I had extremely powerful experiences working with those coaches. Of course, I’d always prefer to meet in person when possible, but since they lived far away from me, I never would have been able to work with them if not over video conference.

As a coach myself, approximately half of my clients are over video conference — and I highly recommend it as an option if there’s not a coach you’d like to work with nearby.

…

I hope this is a helpful comparison. I wanted to make two important caveats, however:

1. The differences between therapy and coaching depend a lot on how you define “therapy” and “coaching.”

I mentioned this above, but it’s worth repeating here: there are many, many types of therapists and coaches out there. As a result, coaching and therapy can be extremely different — there might be very little overlap between a business coach and an art therapist, for example. Or they may have many similarities.

So this comparison is really between a generalized definition of “therapy” (which is a huge field!) and Integral Coaching, because that’s the form of coaching I am most familiar with. I’m a trained Integral Coach (more on that here), and I’ve worked with several Integral Coaches.

Much more important than whether you’re working with a coach or a therapist is the fit with the practitioner themselves. Do you feel comfortable sharing intimate things? Do you feel heard? Do the ideas they share with you resonate?

2. I’m a coach.

I’ll acknowledge that I may be biased since I’m a coach myself. But, I’ve also strived to be as factual as possible. I chose to become a coach, though I considered becoming a therapist for a long time because I mostly wanted to work with functioning and highly functioning people, and because I had such powerful experiences with coaches myself.

But I still believe that therapy can be a fantastic resource. For certain types of people — such as those struggling with serious mental disorders or who need to heal from serious trauma — therapy is truly the best, and only, option. And for those who are functioning or highly functioning, it’s possible for you to see either a coach or a therapist — I have had positive experiences with both. It will simply depend on the experience you’re looking for.

…

Above all, I hope that if you’re struggling, or even if you just feel like you’d like some support, you’ll seek it out. Working with professional coaches or therapists has been extremely useful to me, and I recommend it highly.

If you’re curious about working with me, here’s more about my approach, and here’s how you can schedule a short, free call to hear more about coaching, ask any questions you have, and see if it might be a good fit for you. I’d love to hear from you!

As always, I’m rooting for you. You’ve got this.

Katie

A tip if you'd like to reduce anxiety

I read some remarkably useful advice recently. It’s simple, but I was astonished by how effective it was for me. I thought it might help you, too.

Here it is: “Don’t think too much about your life after dinnertime”.

That advice is from artist and author Austin Kleon. Here’s what else he says about it:

Thinking too much at the end of the day is a recipe for despair. Everything looks better in the light of the morning. Cliché, maybe, but it works.

Kleon is right: it sounds cliché, but it works.

Personally, I’ve noticed that at least 60% of my personal and professional anxiety happens at night.

Implementing this rule doesn’t mean that I’ll never feel worry or self-doubt, but it does mean that I’m less likely to engage with those feelings. Instead of spending an hour mulling it over, wondering if I should make big changes and how I would implement them, I just think, Well, I know that I tend to feel anxious and doubt myself at night. How about we table this question until the morning?

And then in the morning? You guessed it: It’s not that big of a deal. Either the “problem” isn’t truly a problem, or it can be addressed in doable, non-stressful ways.

I’m in your corner rooting for you.

Katie

What elite athletes can teach us about the "value" of hiring a coach

LeBron James, one of the best basketball players in the world, spends $1.5 million each offseason on professional maintenance and development. Much of that expense is on people who help him identify weaknesses and design and implement new routines in his workouts, nutrition, hydration, physical therapy (cryotherapy, hyperbaric chambers), and more. And it’s working — he’s a 34-year-old athlete who is still at the top of his game.

Tiger Woods, one of the best golfers in the history of the sport, has changed his golf swing not once but four times. These aren’t microscopic changes that no one but the golfer can see; one golf publication compared each change to “razing Buckingham Palace and building the Kremlin in the exact same spot.” He’s done so by working with four different swing coaches.

Tom Brady, still one of the best quarterbacks in the world at 41 years old, has an extreme devotion to his “body coach” Alex Guerrero, who advises the elite athlete on workout routines, nutrition, spirituality, his mental attitude and more.

So many people I talk to feel bashful for embarrassed about admitting that they might need help. But does LeBron James feel embarrassed? No. He knows that getting help is the only way that he will stay at the top of his game. I would assume that Brady and Woods are the same.

If you aren’t an elite athlete, the type of coaching or support you need may be different. And, obviously, your budget won’t be as high as James’, Woods’, or Brady’s. But if you want to keep growing, get past roadblocks, attain mastery, and prevent burnout or breakdown, why not follow the example of people who are at the top of their game?

Why not see asking for help as a sign of strength, or vision, or ambition?

…

And, of course: if you'd like some support to grow more or feel better than you do, hiring a personal coach can be a great choice. If you’re curious about working with me, here's more about my approach, or you could schedule a short, free call with me to ask any questions you have.

You’ve got this.

Katie

Life doesn't feel right? You might be having a "breakdown" (And that might be a good thing)

One of the first lessons I learned when I trained to be a coach was about “breakdowns”. My coaching school, New Ventures West, defines a “breakdown” as “non-obviousness”*.

Take a moment to let that sink in. Breakdown is when you experience non-obviousness.

Something about your life doesn’t feel right, and it’s not obvious what the problem is.

You are in a new or challenging situation, and it’s not obvious what the next, best move would be.

You know what you should do or want to do, and it’s not obvious why you aren’t doing it.

Most of us intuitively understand that we might be in “breakdown” if something major in our lives was going off the rails —our career or our marriage, for example. But the radical thing about defining breakdown as “a state of non-obviousness” is that if we’re paying attention, we are all frequently in a breakdown.

Think about it. If we’re really paying attention, we probably find ourselves in a state of non-obviousness perhaps even multiple times a day.

It might not be obvious what the best way is to deal with a challenging relationship at work.

It might not be obvious what the best way is to prioritize our personal finances.

It might not be obvious what our goals are at work or at home.

That doesn’t necessarily mean that we’re failing at any of those things. Most of us are quite competent people who make it through just fine, most of the time! It just means that if we were really paying attention, we’d notice that there are more situations than we thought when we’re not really sure what is best for us.

And when things aren't obvious, life can get really interesting. We can question assumptions and ideas that we thought were set in stone. We can explore and try new things, from a genuinely curious place. We can get advice and support because we don't expect to be able to figure it all out on our own.

If we let ourselves be in a breakdown, it can sometimes lead us to truly thriving in the world.

…

Which leads me to ask: In what areas of your life are you currently experiencing “non-obviousness”? How could you behave differently, by embracing that reality?

As always, I’m rooting for you. You’ve got this.

Katie

* New Ventures West was inspired by Heidegger’s work in developing this definition of “breakdown.” I am not a Heidegger scholar, but my understanding is that it comes from a combination of two terms in his work: “breakdown of transparency” and “breakdown of obviousness”.

For when you're feeling like you aren't doing enough

I increasingly believe that one of the most important life skills you can cultivate is the Art of Partial Credit.

Sure, you’ll feel fantastic when you do your entire, ideal morning routine,

Or when you follow your eating plan perfectly,

Or when you check everything off your to-do list.

But then something will happen. Something unexpected. And you won’t be able to perfectly follow your plans.

What do you do then? Will you give up on your plans and browse the internet while mindlessly eating cookies for breakfast?

Or will you go for partial credit?

I know you’ve got this. I’m rooting for you.

Katie

Read this if you're struggling to make a decision

Here’s a hard but important truth: Sometimes you have to choose.

Sometimes you have to choose between having time to rest and recharge vs. doing something exciting and fun.

Between pursuing thinness vs. pursuing sanity around food.

Between pursuing a career you love vs. a career that will make your life feel balanced.

Is it possible to have both? Maybe! Eventually! In some form!

But here in the present moment, we usually have to prioritize. We need to know what we’ll choose when push comes to shove. Even if it feels like both things are extremely important, there’s usually one thing that takes precedence, even subconsciously.

But why let it be subconscious? Life is easier if you make your prioritization explicit. That way, you don’t have to be jealous of other people who are thin or have a high-earning career, for example, if you are choosing to prioritize sanity around food or a balanced work life. Every choice has trade-offs, and you can make peace with yours.

Prioritizing is an act of kindness. It is saying to yourself: I will accept the limitations of reality.

What are your dreams for your life? How can you prioritize them, for the week ahead?

How can you give yourself a break?

As always, I’m rooting for you. You’ve got this.

Katie

A reminder, when you're trying to figure out what you want in life

Here’s a Sunday Reminder:

You probably do know.

As in, if there’s something in your life — in your career or a relationship or personal choices — that you “don’t know” what to do about, there’s a good chance that you know more than you think.

Have you taken time to really be alone, unstimulated, and reflect on the question? There’s a good chance you’ll be able to get clear on:

What you do know right now

What experiments or actions you need to try next, in order to find out more

Who or what might be able to support you in figuring out more

What is un-knowable for the moment

Many of us use “I don’t know” as shorthand for “this is a hard situation.” But hard situations are precisely when we shouldn’t lie to ourselves about what we know!

You probably know a lot already. You probably know plenty to get started.

As always, I’m rooting for you. You’ve got this.

Katie

A "generally useful prescription": 6 ways to improve your mental health

Oh, you’re feeling anxious?

Stuck?

Frustrated?

Like something isn’t quite right in your life?

Oh, you’re convinced you need to leave your job?

Or break up with your partner?

Or completely change some other aspect of your life?

Immediately?

Before you give your two weeks’ notice or throw out all the sugar in your house, may I suggest the following generally useful prescription?

This prescription is like Advil for a variety of life’s emotional and existential pains. It solves some issues completely, and for others, it reduces the pain temporarily — which is nonetheless extremely useful: if you’re in that panicky, anxious place, it’s likely that you’ll make decisions and take actions that are not the best possible choices for you. So instead, take this prescription, and consult with yourself (or me!) two days later.

A generally useful prescription:

Once a day, for two consecutive days (Did you catch that? One day is not enough! TWO CONSECUTIVE DAYS.) :

1. Thirty minutes of gentle, pleasurable exercise.

A walk outside counts. So does yoga. Boot camp class doesn’t. The goal is to gently burn off some stress while helping you be more aware of your body. Sometimes if an exercise is too hard, you’ll somewhat “leave” your body in order to “push through” to the end.

2. Thirty minutes of journaling.

You can journal about the things you’re worried about, the things you want to change or achieve, or anything at all. The act of writing helps you stop ruminating and actually process how you’re feeling and what you actually want to do about it. More instructions here.

3. Shower and attend to your appearance.

“Attending to your appearance” means different things to different folks, but the idea is that you should do whatever makes you feel juicier about your physical body. Wear some clothes you like, style your hair in a way that is appealing to you, or wear some makeup or jewelry if those are things you enjoy. It sounds trivial, but it makes a difference.

4. Get 8 hours of sleep — minimum.

This is not a joke.

5. Feed yourself food that is nourishing and pleasurable.

Even if you don’t have time to cook, now is the time to splurge a little bit on some lovely, tasty food that also makes you feel good. And yes, some amount of purely delicious food — like a perfect cookie — is nourishing, too.

6. Cut out all non-essential internet activities.

You have to send emails at work? That’s fine. But no internet for pleasure. This might be the hardest thing to do of all of the things on this list, frankly — most of us in the modern world have a lot of compulsions around our internet usage. But you can use that time to do your journaling and walking and showering and sleeping, and probably still have some time left over to read that book that has been sitting on your nightstand for months.

…

It’s easy to skim over this list. It’s easy to think, oh, I do some of that already.

But are you feeling anxious or frustrated or stuck or not right?

I dare you.

I dare you to try these, 100%, and see how you feel.

I will not discuss “Do I need to make a major life change?” or “Am I a failure?” until these actions have been completed, in full, for two consecutive days. (Reminder: One day is not enough. TWO CONSECUTIVE DAYS).

As I said above, it may not fix everything, but it will significantly reduce stress and anxiety, and give you more clarity of mind — hopefully, enough clarity of mind to come up with a wise sense of the right next steps for you.

As always, I’m rooting for you. You’ve got this.

Katie

What it means if you're struggling in your life

Sometimes my clients are frustrated with themselves. They’re smart and competent, and they may feel embarrassed that they’re struggling.

Sometimes it seems like I’m the only person who is breaking down like this, they tell me. It feels like I’m the only person who needs to grow.

In those situations, I tell them about Osteoblasts and Osteoclasts.

Osteoclasts and Osteoblasts are bone cells that are always present in our bodies. Osteoclasts break down bone tissue, and Osteoblasts rebuild it. Bones constantly need to be repaired and remodeled to better address the many stressors our bodies face, and you can’t rebuild without having broken down the bone tissue first.

Osteoclasts and Osteoblasts work as a continuous team:

Break down.

Repair and rebuild.

Break down.

Repair and rebuild.

What a perfect, natural process. Break down, rebuild. Again and again.

Which is to say: our bodies understand that things must break down all the time so that we can rebuild to be more efficient, more effective, and stronger.

Why not us?

As always, I’m rooting for you. You’ve got this.

Katie

Why I was scared to quit my job, and what helped me

I’m afraid that I’ll become a homeless person, and that I won’t have health insurance.

I blurted out that sentence to my coach, trying to explain why I was so afraid to leave my job and take some time off. It felt kind of dumb after it came out of my mouth — it sounded so extreme.

But it did capture the real lot of fear I had: I was so burnt out at my job that my desire for rest seemed infinite. I was pretty sure if I listened to those desires, I’d never work again. And then I’d run out of money and have to live on the street and…

But my coach was looking at me calmly. In the most compassionate way in the world, she asked me: “Katie, is health insurance something that you want?”

“Yes,” I told her.

“Well then, I think you can trust that some deep part of you will take care of yourself. Just like you need rest and some space, you also need health insurance.”

She continued, in the friendliest way, “Don’t you think that when push comes to shove, you’ll do what you need to, in order to get what you need? Like, if you get low on money and you really have to, you’ll get a job that you don’t prefer, so you can make sure to get the health insurance you need?”

“Don’t you think that you will take care of yourself when it comes down to it?”

I sat there, dumbfounded in my chair, soaking up how right she was.

…

To be clear, the point of this story isn’t “quit your job!”. That’s not always the right decision. (Far from it!) Rather, the point is this: You will take care of yourself.

So many of us have similar fears that we would blurt out if we were being truly honest:

If I let myself slow down at work, I’ll never accomplish anything, ever.

If I let myself turn down social events as much as I want to, I’ll never go out again, all my friends will abandon me, and I’ll be a complete loner.

If I let myself eat as many pumpkin cinnamon rolls as I really want, I’ll never stop eating until I gain 200 pounds.

I’ve heard all of these from my clients in the past, and I’ve certainly felt them myself!

But you know what? It’s typically not true that our desires are infinite.

Yes, we want a more balanced relationship with work, but we also want the pride of making an impact.

Yes, we want to rest at home alone, but we do also want to see our friends.

Yes, we want pumpkin cinnamon rolls, but we also want to feel good in our bodies.

So, yes, if we listen to our desires for a while, we may end up staying home or eating more cinnamon rolls than usual. But, eventually, we will reconnect with the other things we want, and find a balance that makes sense.

That certainly happened to me. I eventually left my job and took a few months to completely rest and look around. Then, as I started to feel more rested, making sure that my bank account was healthy became an increasingly higher priority. So I found part-time work, and later, full-time work.

With health insurance, of course.

So I’d like to ask you: What truthful desires are you afraid of because they seem “too big”?

I know you’ve got this.

Katie